Somalia, Kenya to resolve diplomatic row over maritime boundary, unclear whether Mogadishu accepted to withdraw its case at ICJ

Ethiopian Prime Minister brokered the deal between Somalia and Kenya, ending a month-long diplomatic row over maritime boundary.

By The Star Staff Writer

MOGADISHU – Somalia’s President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed Farmajo and his Kenyan counterpart agreed on Wednesday to restore ties between their two nations, ending a three-week-long diplomatic row over their maritime boundary that threatened to plunge the two neighbors into a broader conflict.

“The presidents (of Kenya and Somalia) agreed to restore and strengthen the relationship and cooperation of the two countries, which are based on respect and full cooperation on security, economy and movement of people and business,” said a statement from President Farmajo’s office.

The statement was both short on specifics and devoid of basic details, prompting many to question the real agenda of the leaders’ meeting in Nairobi. Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta has not publicly commented on the matter, even though his country’s justification to kick out Somalia’s Ambassador last month was the dispute over the maritime boundary between Somalia and Kenya.

Farmajo’s office didn’t also say whether Mogadishu accepted Kenya’s request for an out-of-court settlement for the Somali case at the International Court of Justice. The Presidency’s statement just lauded the role of Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in “re-establishing the friendly relationship between Somalia and Kenya” and termed the talks between Farmajo and Kenyatta “fruitful.”

The two leaders on Wednesday held — through Abiy’s mediation — their first face-to-face talks since the eruption of a diplomatic spat on Feb. 16, when Kenya expelled Somalia’s Ambassador to Nairobi and recalled its envoy over unsubstantiated claims that the Horn of Africa nation auctioned Kenyan offshore blocks in London on Feb. 7.

Abiy, who is the chairman of the regional bloc of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, or IGAD, hosted President Kenyatta in Addis Ababa over the weekend before inviting President Farmajo to Addis Ababa on Tuesday to further “facilitate the first face to face discussion.”

President Farmajo and Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy then travelled together from the Ethiopian capital and arrived in Nairobi on Tuesday night.

Somalia and Kenya “agreed to work towards peace & to take measures in addressing particular issues that escalated the tensions,” said Prime Minister Abiy’s office in a Twitter message on Wednesday. The three leaders discussed “extensively on the source of the two countries(‘) dispute,” said the message.

President Farmajo’s office said on Tuesday that the “main objective” of the Somali leader’s visit to Nairobi was “to restore and strengthen diplomatic relations with the Republic of Kenya.”

Somalis, who are traditionally leery of Ethiopia’s role in their country, expressed concern about President Farmajo’s hasty decision to go Nairobi, which instigated the diplomatic crisis after it claimed without producing any hard evidence that Somalia auctioned offshore blocks belonging to Kenya.

Abdirahman Abdishakur Warsame, the chairman of Wadajir Party, ripped President Farmajo’s statement, saying it is “an abuse of the intellect of the Somali public for the Somali Presidency to say that ‘Kenya and Somalia have reconciled’ without mentioning the core issue that caused the dispute.”

“It’s a national and constitutional obligation to tell the Somali public the truth,” said Warsame in a post on his Facebook page. “The president has to tell the truth about the talks he had held in Addis Ababa and Nairobi.”

Warsame called on the Somali media to investigate what President Farmajo did during his visits to Ethiopia and Kenya.

A former Somali Ambassador blasted President Farmajo’s decision to fly with Abiy to Nairobi on the same Ethiopian plane.

“The right diplomatic procedure was #Abiy (and) #Kenyatta to travel to Mogadishu,” said Idd Bedel Mohamed, a former Ambassador at Somalia’s Mission to the United Nations in New York, referring to the Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta. “…Traveling to the country that started the problem diplomatically means Somalia was at fault and Kenya is being calmed down.”

Others saw the trip to Nairobi as a “trap” Abiy laid for President Farmajo who until recently resisted Kenya’s overtures for an out-of-court settlement for the maritime dispute between Somalia and Kenya that is being adjudicated at the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

Mukhtar Ainashe, a former adviser to former President Sheik Sharif Sheik Ahmed, warned of a “brutal military force” and “violence” if President Farmajo withdraws the Somali case from the ICJ. “He will be deposed & arrested on national treason charges,” he said. “He should apply political asylum in Kenya!”

But Abdinur Mohamed Ahmed, director of communications at the office of President Farmajo, sought to assuage Somali concerns, saying Somalia’s lands are not open for discussions.

“No negotiation and talk on the case at the International Court of Justice on (the delineation of) maritime (boundaries),” said Ahmed in a message on his Facebook page. “We will wait for the court’s decision. We will not negotiate an inch of our land.”

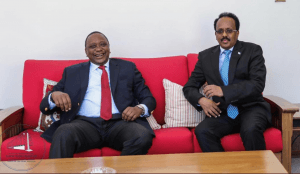

President Farmajo (right) with his Kenyan counterpart, Uhuru, in Nairobi.

President Farmajo (right) with his Kenyan counterpart, Uhuru, in Nairobi.

When Nairobi expelled Somalia’s Ambassador, many analysts saw the move as an unnecessary overreaction aimed at squeezing concessions from Somalia’s weak government, especially after the Kenyan government on Feb. 21 dramatically escalated its maritime row with Somalia and demanded an apology and withdrawal of Somali maps showing offshore blocks offered at the London conference.

The Somali government refused to offer any apology and instead accused Kenya of basing its statement “on a misunderstanding of the facts,” according a Feb. 25 letter from Somalia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Both Somalia and the Norwegian company, Spectrum Geo Ltd., which shot the seismic data presented at the London conference, denied Kenya’s claims. Spectrum carried out two seismic surveys that covered 40,000 kilometers of Somali waters.

The Somali letter, which was a response to Kenya’s complaints, urged the Kenyan government to wait for the ICJ decision, which “will be decided in due course consistent with international law.”

“The Government of Somalia wishes to assure the Government of Kenya that it will respect and comply with the ICJ’s judgment, and trusts that the Government of Kenya will do the same,” said Somalia’s response, urging both sides to refrain from “taking action that may aggravate the dispute.”

Mogadishu also rejected Kenya’s “unfortunate characterization” of Somalia’s earlier statement as “deliberately misleading.”

The two countries have been locked in a maritime dispute since 2009, with Somalia saying its maritime boundary with Kenya lies perpendicular to the coast and Kenya claiming the line of latitude protrudes from its boundary with Somalia.

In 2014, Somalia took its case to the International Court of Justice, requesting the U.N.’s principal judicial organ “determine, on the basis of international law, the complete course of the single maritime boundary dividing all the maritime areas appertaining to Somalia and to Kenya in the Indian Ocean, including the continental shelf beyond 200 [nautical miles]”.

Somalia also asked the court to “determine the precise geographical co-ordinates of the single maritime boundary in the Indian Ocean.”

Kenya suffered a major setback in 2017 after the ICJ agreed to hear the Somali case, rejecting Nairobi’s preliminary objections to its authority to rule on the maritime boundary dispute between the two countries. Fearing that it could lose the case, Kenya has been pushing for direct negotiations, which Somalia resisted, especially after numerous talks that preceded Mogadishu’s decision to sue Kenya yielded no results.

Many Somalis suspect that Kenya’s diplomatic escalation is just a stratagem aimed at shanghaiing Somalia into an out-of-court settlement. Somalis believe that Kenya has taken advantage of their nation’s weakness to lay claim to their waters, whose ownership were not in dispute when Somalia had a strong, functioning government.

Before their departure for the Nairobi talks, Kenya, President Farmajo and Prime Minister Abiy held talks in Addis Ababa that focused on four key issues: Strengthening the region’s peace and security, strengthening the relationship between Somalia and Kenya, continuation of the agreement that allowed Ethiopia last year to invest in four Somali ports and ensuring that Somalia’s northern region joins the ongoing regional peace initiatives.

President Farmajo’s office said Somalia and Kenya have also agreed to fight terrorism and restore peace to the East Africa region. Despite the Nairobi talks’ importance, the Kenyan government remained tight-lipped about its outcome, raising queries about what the leaders actually agreed behind closed doors.